Toward the Plane of the Sacred: Hafftka’s Great Chain of Being

By Michael Brodsky

Click an image to enlarge

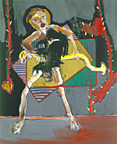

One of the many wonders of Michael Hafftka’s incomparable art is how powerfully it connects performance with the quest for salvation. To perform is to seek redemptive communion with the sacred. And to attain the plane of the sacred one must be willing to take risks—willed risks of self-distortion, contortion, unhingement, isolation. These marks confirm the high seriousness—the irrevocability—of the enterprise. Take, for example, the elegant headliner of “Untitled” (1983), part Nosferatu, part toreador, part virtuoso fiddler, part prestidigitator—in short, performer par excellence.

One of the many wonders of Michael Hafftka’s incomparable art is how powerfully it connects performance with the quest for salvation. To perform is to seek redemptive communion with the sacred. And to attain the plane of the sacred one must be willing to take risks—willed risks of self-distortion, contortion, unhingement, isolation. These marks confirm the high seriousness—the irrevocability—of the enterprise. Take, for example, the elegant headliner of “Untitled” (1983), part Nosferatu, part toreador, part virtuoso fiddler, part prestidigitator—in short, performer par excellence.

And not just a performer but one who is willing—who is compelled—to make himself ridiculous, grotesque, for a shot at salvation. And not just his own salvation but the salvation of the world—your salvation and mine. Performance chez Hafftka is a life-or-death engagement with hostile forces, most conveniently incarnated in the unseen audience waiting for the performer to fall flat on his face. The intense concentration demanded by Nosferatu’s flourish has enabled him to sprout, to secrete, from somewhere in the middle of his forehead a ladder to another plane, the plane of the sacred. (Ladders abound in Hafftka’s universe: see below.) And it is all to the good pictorially that this appendage (which very well may be infinite in length since it is cut off by the frame) is not quite pinpointable—it could be a pair of antennae or an aigrette. Ambiguity invites spectator collaboration and collaboration distracts the spectator from his inherent Schadenfreude—the wish to see the performer fall on his face. In any event, the appendage as ladder is not only his way out but the serendipitous mark of his beauty, the only beauty that matters—beauty as unplanned byproduct of effort. In speaking of a way out, one is reminded of the ape in Kafka’s “A Report to the Academy” who avows: “No, freedom was not what I wanted. Only a way out; right or left, or in any direction; even should the way out prove to be an illusion…Only not to stay motionless with raised arms…” “Only not to stay motionless”: the war cry in Hafftka’s universe.

Brethren to Nosferatu the performer are the buskined figure in black—part cat burglar, part danseur noble, part ventriloquist—of “Grip“, the “Two Figures Jumping“, the bowled-over “Stumble-dancer“, the cantors in “Grand Opening“, “Higher Octave“ and “Congregation“, flayed by the impasto of greasepaint; the naked parties to the “Dress Rehearsal“; the trapeze artist chinning/teething on the bar of hope and his two big-top comrades in “Leap of Faith“; the highwire musicians in “Jamming“, the tormented transvestite and his/her alter ego in “Marshwiggle“, the “Two Knights“ (one being Quixote); the trapezists in “Fly“; and even the defecator in “Decision Making“ (Hafftka’s take on Rodin’s Penseur). All are performers because they know, or because their bodies tell them they know, that attainment of the sacred is contingent on performance—on making the effort. Performance—the dancer’s willing him- or herself to become indistinguishable from the dance—is the only ladder of ascension to the plane of the sacred.

Mircea Eliade, in Shamanism, emphasizes the importance of the ladder as “an instrument of ontological passage from one mode of being to another—of transcendence—of attainment to the world of the gods, of power, of reality—a world saturated with being. In short, the world of the sacred.” Redemption is possible only through immersion in the warm bath of authentic being.As attested by the myths of the peoples of Africa, Oceania and North America, by Brahmanic sacrificers and by the instructions of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, “ladders facilitate the descent of the gods to earth and ensure the ascent of the dead man’s soul. Yet even if actual ladders and gangways appear frequently in Hafftka’s works, they may not be trustworthy or efficacious and, as proof of this, they seem either to be ignored or held in reserve as a last resort—if the performative activity of self as ladder fails.

The self in transformative motion—the motion craved by Kafka’s agonizedly articulate ape—is the only ladder, up or down, that counts. Even more crucial is the question whether Hafftka’s stock company are in a condition or at a stage to believe in redemption through attainment of the plane of the sacred. Do the ladders perhaps represent mere bric-a-brac, expendable artifacts of a time before Holocausts and slave trades when the myth of transcendence was still plausible.

The self in transformative motion—the motion craved by Kafka’s agonizedly articulate ape—is the only ladder, up or down, that counts. Even more crucial is the question whether Hafftka’s stock company are in a condition or at a stage to believe in redemption through attainment of the plane of the sacred. Do the ladders perhaps represent mere bric-a-brac, expendable artifacts of a time before Holocausts and slave trades when the myth of transcendence was still plausible.

But there are other means besides performance to self-transform in pursuit of the sacred. In “Man and Elephant”, man has taken a first step towards fusion with beast—the elephant’s exquisite pink and bluegrey trunk has become his master’s prosthetic hip and leg. His transition from man to beast might very well contitute his version of “ontological passage from one mode of being to another.”

In “Fix”, the addict, too, is in transit:

In “Fix”, the addict, too, is in transit:

he constitutes the missing link (we will investigate this concept as it relates to Hafftka’s work more thoroughly below) between his pre-fix mummified and prostrate self convulsed with need and the self soon to be immersed in a warm bath of blood-red euphoria from whom he is separated by the thinnest of thin (dovegrey) lines. In “Private Affairs”, the copulators hope, through fusion, to be each other’s ladders to another dimension; the figure at the extreme right is trying to achieve as much through prayer.

he constitutes the missing link (we will investigate this concept as it relates to Hafftka’s work more thoroughly below) between his pre-fix mummified and prostrate self convulsed with need and the self soon to be immersed in a warm bath of blood-red euphoria from whom he is separated by the thinnest of thin (dovegrey) lines. In “Private Affairs”, the copulators hope, through fusion, to be each other’s ladders to another dimension; the figure at the extreme right is trying to achieve as much through prayer.

The feisty streetwalking vaudevillian of “Frame of Mind”, is perhaps the most delightful—the most efficacious—of Hafftka’s transit figures: she “divides her time” between the body-bisecting canvas of which she, or her torso, is the subject, and the “real” world of spiked, viny carmine bellpulls. She knows neither domain will provide by itself a way out, much less access to the sacred—only life-or-death leaps from one domain to the other and back again can be expected to begin to do that.

And to protect herself from the inevitable spikelike outrage at her traitorousness from the denizens of both domains, she wields a pipelike truncheon that is itself an embodiment of flux—pterodactyl at one end and sheet anchor at the other. Or, perhaps, having passed through her body, this creature-object has become infected with her appetite for unlocalizability.

And to protect herself from the inevitable spikelike outrage at her traitorousness from the denizens of both domains, she wields a pipelike truncheon that is itself an embodiment of flux—pterodactyl at one end and sheet anchor at the other. Or, perhaps, having passed through her body, this creature-object has become infected with her appetite for unlocalizability.

To conclude, any act that allegorizes the movement from one plane to another might very well qualify as a ladder to the domain of the sacred. Hafftka--a deeply religious artist, a mystic with both feet on the ground, so to speak, playful, and without rancor—offers his players a wide range of possible ways in and ways out. We catch all of Hafftka’s creatures in extremis. There are significant confirmatory features of that crisis that appear in painting after painting.

First, mutilation of the male body. It is specifically the males that undergo mutilation, often willingly. In the exquisite “Husband and Wife”, the husband’s right arm and lower body are amputated by the suffusing darkness, although his wife confronts the “camera” head on, all of her limbs forthrightly, almost defiantly, intact. The male feels the appropriateness, the inevitability, of partial obliteration in the presence of the monolithic female: she has body enough for two. In “Fly” and “Dress Rehearsal”, the feet of the topmost figures are amputated by the top of the canvas. The leg of one of the Two Knights terminates in a kind of stump and the other leg is well on its way to atrophy; the decision maker is missing his right foot. Most straightforwardly, in “Untitled” (1991), the male figure loses one leg to the lustrous dark at knee level and the other leg begins to give up the ghost somwhere below mid-calf.

Moreover, the entanglement of intimacy, the indistinguishability of bodies generated by copulation, can effect a form of mutilation. In “Group”, which of the figures can lay claim to a complete set of limbs? How many postcoital figures are there in “Ninety Degrees” and which, if any, are anatomically replete? Igor in “Igor and Romulus” does, it is true, sport a powerfully virile and visibly intact physique but who’s to say how much of that intactness is ascribable to the watchful presence of the dog at his feet and/or the horizontal spear or oar or hockey stick (a bit like the bar in “Leap of Faith”) that he wields apotropaically at crotch level?

At the same time, the ambiguities connected with anatomy in so many of the paintings can be considered the fruits of a cunning formal strategy. Forced to confront a disturbing enigma centered around ablation, amputation and lack, the spectator must work to perceptually repair and rehabilitate injury and insult.

He then becomes a collaborator in the production of the artwork. Hafftka’s painting becomes the recruited spectator’s very own work in progress. Among other things, he must determine at what point in the surrender to fusion with another or with an activity, individual identity, or corporeal intactness, is lost. Such work mimics under controlled conditions our toilsome daily doom of domesticating an overabundance of disorienting data, as minute by minute, year by year, we joltingly go about rectifying and redrawing our foregone conclusions before their misguidedness proves lethal. Hafftka’s uncompromising art permits us to be reconciled to that doom and even to take pleasure in it, at least within the domain of his paintings. The disorientations, the entangling enigmas patent in his work, educate us—enable us to return to the world strengthened and ennobled. The anatomical mutilations, distortions, deformations, then, may very well indicate that intactness and completeness were never intended. For Hafftka is one of those creators for whom essence is incompatible with academic notions of health and wholeness.

He then becomes a collaborator in the production of the artwork. Hafftka’s painting becomes the recruited spectator’s very own work in progress. Among other things, he must determine at what point in the surrender to fusion with another or with an activity, individual identity, or corporeal intactness, is lost. Such work mimics under controlled conditions our toilsome daily doom of domesticating an overabundance of disorienting data, as minute by minute, year by year, we joltingly go about rectifying and redrawing our foregone conclusions before their misguidedness proves lethal. Hafftka’s uncompromising art permits us to be reconciled to that doom and even to take pleasure in it, at least within the domain of his paintings. The disorientations, the entangling enigmas patent in his work, educate us—enable us to return to the world strengthened and ennobled. The anatomical mutilations, distortions, deformations, then, may very well indicate that intactness and completeness were never intended. For Hafftka is one of those creators for whom essence is incompatible with academic notions of health and wholeness.

In his magnificent essay on Rodin—specifically on Rodin’s private mausoleum of intentionally imperfect late sculptures—sculptures to which nothing was more inimical than the “finishing touches” beloved of conventional artists—Leo Steinberg notes that inasmuch as the sculptor strove not so much to model a body in motion as clothe “a motion in body” and in no more body than the motion required to fulfill itself—inasmuch as what Rodin was after was “not really a human body, but a body’s specific gesture”—he strove to retain “just as much of the anatomical core as that gesture need[ed] to evolve.” Clothing a motion in body and retaining just so much of the body’s core as the motion needs to fulfill itself certainly constitute one essential task that Hafftka assigns himself in many of the paintings for an attempted Leap of Faith (this could be the title of every one of Hafftka’s paintings) into the domain of the sacred with or without ladder or chinning bar is more likely to succeed with the barest minimum of anatomical baggage.

Another particularly disquieting hallmark of the Hafftkaesque crisis is the presence in several of the paintings of what one might call the missing link—an atavistic creature representing a sort of golemlike point of intersection between being and nonbeing, between man and animal, between heaven and hell—an infinitely gentle, perhaps infinitely suffering embryon that might at the same time be capable of devastating malevolence simply in order to, willy-nilly, persist in its own being. I’m thinking here of the tiny sinuously graceful entity on the extreme right in “The Selecting Hand” palpatingly traversing a trunk or bollard; the poignantly lemurlike head with quizzically haunted eyes and foreshortened arms crossed just below its neck in “History Lesson”, a kind of simian infanta; and the eye-patched, grass-skirted songstress in “Jamming”, with her floating gonadal insignia.

“Gumby”—does this painting allude to the animated cartoon character created by Art Clokey (a former Episcopal seminarian! and therefore consanguineous with Hafftka the Kabbalist)?—seems to be “all about” such creatures. In this category one may also include the two purposefully blurred forms blessed by the Roualtlike Christ in “The Blessing” and the pathos-laden monkey cum donkey like figure in profile at the extreme right in “Dead End”, Hafftka’s only excursion into film noir (but film noir adroitly mated with A Midsummer Night’s Dream). These creatures are depicted with a dispassionate tenderness and hardnosed affection reminiscent of Tod Browning’s Freaks and Bunuel’s Viridiana, Nazarin and Los Olvidados (Hafftka’s beings, too, are forgotten ones). But more to the point is Eisenstein, specifically the Eisenstein of Potemkin. I’m thinking of the passage where the people of Odessa are rushing towards the harbor to welcome the incoming battleship. The pageant would have itself been mutilated, crippled, if it hadn’t embraced his exemplary nisus.

In Kafka’s “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk,” (as in Hafftka’s paintings, this is a world of beings not quite human, not quite animal) the crucialness to any community of the ostensibly marginal missing link is stressed with exquisite succinctness: “…it turns out,” says the narrator, “that we have overlooked the art of cracking nuts because we are too skilled in it…and that this newcomer to it first shows us its real nature, even finding it useful in making his efforts to be rather less expert in nut-cracking than most of us” (the italics are mine). Since the legless cripple is less expert than the rest of us in racing towards the harbor, he allows us to recuperate the essence of that act and by extension all human acts. The Great Chain of Being was, according to Lovejoy, “a conception of the plan and structure… of the universe” as “composed of an immense, or…of an infinite, number of links ranging in hierarchical order from the meagrest kind of existents, which barely escape non-existence, through ’every possible’ grade up to the highest possible kind of creature.”

Eliminating “even one link in the series…would be a general dissolution of the cosmic order.”

Eliminating “even one link in the series…would be a general dissolution of the cosmic order.”

In Lovejoy’s view, the remark of Plotinus to the effect that it is better that one animal should be eaten by another than it should never have existed at all” takes this concept to its logical (and poignantly chilling) conclusion.

The concept was so compelling that from at least of the middle of the eighteenth century down to Darwin’s era, the quest for the missing links to plug the gaps in the Chain enthralled not only professional naturalists but the general public.

The concept was so compelling that from at least of the middle of the eighteenth century down to Darwin’s era, the quest for the missing links to plug the gaps in the Chain enthralled not only professional naturalists but the general public.

Pandering to this insatiable curiosity, no less a mass-market psychologist than P.T. Barnum (in 1842) advertised among his Museum attractions the “preserved body of a Feejee Mermaid” as well as “the Ornithorhinicus, or the connecting link between the seal and the duck…” Hafftka has a particular affection—perhaps tender respect, perhaps lacerated awe, are better terms—for these “meagre existents”,

Pandering to this insatiable curiosity, no less a mass-market psychologist than P.T. Barnum (in 1842) advertised among his Museum attractions the “preserved body of a Feejee Mermaid” as well as “the Ornithorhinicus, or the connecting link between the seal and the duck…” Hafftka has a particular affection—perhaps tender respect, perhaps lacerated awe, are better terms—for these “meagre existents”,

whose very rudimentariness, whose almost coy refusal of any preassigned place on the evolutionary scale, seem to bespeak a secret knowledge of the unspeakable, a communion denied to humans with the domain of some sacred plane hospitable to the enactment of sacrifical rites. Perhaps he is so connected because he senses that beneath their attenuatedness, their shrinkage before our eyes at an ever-increasing rate (the real in Hafftka is what is on the heady verge of disappearance), is what the sixteenth century Kabbalist Moses Cordovero referred to, in speaking of the golem, as “a special kind of naked vitality.”

whose very rudimentariness, whose almost coy refusal of any preassigned place on the evolutionary scale, seem to bespeak a secret knowledge of the unspeakable, a communion denied to humans with the domain of some sacred plane hospitable to the enactment of sacrifical rites. Perhaps he is so connected because he senses that beneath their attenuatedness, their shrinkage before our eyes at an ever-increasing rate (the real in Hafftka is what is on the heady verge of disappearance), is what the sixteenth century Kabbalist Moses Cordovero referred to, in speaking of the golem, as “a special kind of naked vitality.”

It is these marginals who—by virtue of their very marginality!—seem to hold the key to the mystery of Hafftka’s art. It is they who have been elected to secrete his paintings’ untellable tale. In fact, Hafftka seems to have the sort of relation to all his creatures—but most potently and poignantly these meagre existents—that the medieval Kabbalist had to his golem. As Gershon Scholem notes in The Kabbalah and its Symbolism, golem-making is dangerous not because of the overwhelming and unstoppable powers emanating from the golem cum sorcerer’s apprentice but because of “the tension which the creative process arouses in the creator himself.”

It is these marginals who—by virtue of their very marginality!—seem to hold the key to the mystery of Hafftka’s art. It is they who have been elected to secrete his paintings’ untellable tale. In fact, Hafftka seems to have the sort of relation to all his creatures—but most potently and poignantly these meagre existents—that the medieval Kabbalist had to his golem. As Gershon Scholem notes in The Kabbalah and its Symbolism, golem-making is dangerous not because of the overwhelming and unstoppable powers emanating from the golem cum sorcerer’s apprentice but because of “the tension which the creative process arouses in the creator himself.”

Through this ritual which ideally represents an act of creation purely on the plane of thought designed to culminate in mystical ecstasy, the creator challenges God as the creator and thereby introduces the viruses of idolatry and polytheism among his fellow men. Hafftka alerts us to the tremendous danger involved in creating his missing links who, by lurking (without necessarily knowing they lurk) on the periphery of the spectacle, provoke a disquieting mixture of pity and fear in the spectator that calls the entire spectacle into question. He also infects us with his own temptation to worship them as conduits to and embodiments of the sacred and thereby escape from the burden of choosing one’s own “motion clothed in body” as pathway to that domain.

I want to conclude with a word about the titles of Hafftka’s remarkable works. In a number of his paintings the titles are in dialectical counterpoint with the content and become thereby a part of the content. The content of a painting like “Down to Earth” indicts the figurative meaning of the title (“natural, without pretense”) since the subject of the work—a fugitive from a chain gang crawling through a swamp of reeds that impale his prostrate and desperate form—is literally down to earth. But not only does the tension between figurative and literal meanings in relation to content enrich the work through the effort of the spectator to see that content in the key of the literal meaning of the title , but the very fact that the figurative meaning cannot be banished entirely— must somehow be “forgiven”—saves the work from tendentiousness: the grimmest theme is suddenly infected with a playful and absurd blandness which paradoxically and in the nick of time rescues the depiction of such excruciation from self-parody. The contest between figurativity and literalness thus becomes a prophylactic device. Only a truly exceptional artist could manage such a graceful reconciliation of contraries. This all-encompassing gesture is especially moving since the last thing in the world one could imagine Hafftka and Hafftka’s work having any truck with is blandness.

© Michael Brodsky 2004

Home Resume

Resume Bio

Bio

One of the many wonders of Michael Hafftka’s incomparable art is how powerfully it connects performance with the quest for salvation. To perform is to seek redemptive communion with the sacred. And to attain the plane of the sacred one must be willing to take risks—willed risks of self-distortion, contortion, unhingement, isolation. These marks confirm the high seriousness—the irrevocability—of the enterprise. Take, for example, the elegant headliner of “Untitled” (1983), part Nosferatu, part toreador, part virtuoso fiddler, part prestidigitator—in short, performer par excellence.

One of the many wonders of Michael Hafftka’s incomparable art is how powerfully it connects performance with the quest for salvation. To perform is to seek redemptive communion with the sacred. And to attain the plane of the sacred one must be willing to take risks—willed risks of self-distortion, contortion, unhingement, isolation. These marks confirm the high seriousness—the irrevocability—of the enterprise. Take, for example, the elegant headliner of “Untitled” (1983), part Nosferatu, part toreador, part virtuoso fiddler, part prestidigitator—in short, performer par excellence.

The self in transformative motion—the motion craved by Kafka’s agonizedly articulate ape—is the only ladder, up or down, that counts. Even more crucial is the question whether Hafftka’s stock company are in a condition or at a stage to believe in redemption through attainment of the plane of the sacred. Do the ladders perhaps represent mere bric-a-brac, expendable artifacts of a time before Holocausts and slave trades when the myth of transcendence was still plausible.

The self in transformative motion—the motion craved by Kafka’s agonizedly articulate ape—is the only ladder, up or down, that counts. Even more crucial is the question whether Hafftka’s stock company are in a condition or at a stage to believe in redemption through attainment of the plane of the sacred. Do the ladders perhaps represent mere bric-a-brac, expendable artifacts of a time before Holocausts and slave trades when the myth of transcendence was still plausible. In “Fix”, the addict, too, is in transit:

In “Fix”, the addict, too, is in transit:

he constitutes the missing link (we will investigate this concept as it relates to Hafftka’s work more thoroughly below) between his pre-fix mummified and prostrate self convulsed with need and the self soon to be immersed in a warm bath of blood-red euphoria from whom he is separated by the thinnest of thin (dovegrey) lines. In “Private Affairs”, the copulators hope, through fusion, to be each other’s ladders to another dimension; the figure at the extreme right is trying to achieve as much through prayer.

he constitutes the missing link (we will investigate this concept as it relates to Hafftka’s work more thoroughly below) between his pre-fix mummified and prostrate self convulsed with need and the self soon to be immersed in a warm bath of blood-red euphoria from whom he is separated by the thinnest of thin (dovegrey) lines. In “Private Affairs”, the copulators hope, through fusion, to be each other’s ladders to another dimension; the figure at the extreme right is trying to achieve as much through prayer.

And to protect herself from the inevitable spikelike outrage at her traitorousness from the denizens of both domains, she wields a pipelike truncheon that is itself an embodiment of flux—pterodactyl at one end and sheet anchor at the other. Or, perhaps, having passed through her body, this creature-object has become infected with her appetite for unlocalizability.

And to protect herself from the inevitable spikelike outrage at her traitorousness from the denizens of both domains, she wields a pipelike truncheon that is itself an embodiment of flux—pterodactyl at one end and sheet anchor at the other. Or, perhaps, having passed through her body, this creature-object has become infected with her appetite for unlocalizability.

He then becomes a collaborator in the production of the artwork. Hafftka’s painting becomes the recruited spectator’s very own work in progress. Among other things, he must determine at what point in the surrender to fusion with another or with an activity, individual identity, or corporeal intactness, is lost. Such work mimics under controlled conditions our toilsome daily doom of domesticating an overabundance of disorienting data, as minute by minute, year by year, we joltingly go about rectifying and redrawing our foregone conclusions before their misguidedness proves lethal. Hafftka’s uncompromising art permits us to be reconciled to that doom and even to take pleasure in it, at least within the domain of his paintings. The disorientations, the entangling enigmas patent in his work, educate us—enable us to return to the world strengthened and ennobled. The anatomical mutilations, distortions, deformations, then, may very well indicate that intactness and completeness were never intended. For Hafftka is one of those creators for whom essence is incompatible with academic notions of health and wholeness.

He then becomes a collaborator in the production of the artwork. Hafftka’s painting becomes the recruited spectator’s very own work in progress. Among other things, he must determine at what point in the surrender to fusion with another or with an activity, individual identity, or corporeal intactness, is lost. Such work mimics under controlled conditions our toilsome daily doom of domesticating an overabundance of disorienting data, as minute by minute, year by year, we joltingly go about rectifying and redrawing our foregone conclusions before their misguidedness proves lethal. Hafftka’s uncompromising art permits us to be reconciled to that doom and even to take pleasure in it, at least within the domain of his paintings. The disorientations, the entangling enigmas patent in his work, educate us—enable us to return to the world strengthened and ennobled. The anatomical mutilations, distortions, deformations, then, may very well indicate that intactness and completeness were never intended. For Hafftka is one of those creators for whom essence is incompatible with academic notions of health and wholeness.

Eliminating “even one link in the series…would be a general dissolution of the cosmic order.”

Eliminating “even one link in the series…would be a general dissolution of the cosmic order.”

The concept was so compelling that from at least of the middle of the eighteenth century down to Darwin’s era, the quest for the missing links to plug the gaps in the Chain enthralled not only professional naturalists but the general public.

The concept was so compelling that from at least of the middle of the eighteenth century down to Darwin’s era, the quest for the missing links to plug the gaps in the Chain enthralled not only professional naturalists but the general public.

Pandering to this insatiable curiosity, no less a mass-market psychologist than P.T. Barnum (in 1842) advertised among his Museum attractions the “preserved body of a Feejee Mermaid” as well as “the Ornithorhinicus, or the connecting link between the seal and the duck…” Hafftka has a particular affection—perhaps tender respect, perhaps lacerated awe, are better terms—for these “meagre existents”,

Pandering to this insatiable curiosity, no less a mass-market psychologist than P.T. Barnum (in 1842) advertised among his Museum attractions the “preserved body of a Feejee Mermaid” as well as “the Ornithorhinicus, or the connecting link between the seal and the duck…” Hafftka has a particular affection—perhaps tender respect, perhaps lacerated awe, are better terms—for these “meagre existents”,

whose very rudimentariness, whose almost coy refusal of any preassigned place on the evolutionary scale, seem to bespeak a secret knowledge of the unspeakable, a communion denied to humans with the domain of some sacred plane hospitable to the enactment of sacrifical rites. Perhaps he is so connected because he senses that beneath their attenuatedness, their shrinkage before our eyes at an ever-increasing rate (the real in Hafftka is what is on the heady verge of disappearance), is what the sixteenth century Kabbalist Moses Cordovero referred to, in speaking of the golem, as “a special kind of naked vitality.”

whose very rudimentariness, whose almost coy refusal of any preassigned place on the evolutionary scale, seem to bespeak a secret knowledge of the unspeakable, a communion denied to humans with the domain of some sacred plane hospitable to the enactment of sacrifical rites. Perhaps he is so connected because he senses that beneath their attenuatedness, their shrinkage before our eyes at an ever-increasing rate (the real in Hafftka is what is on the heady verge of disappearance), is what the sixteenth century Kabbalist Moses Cordovero referred to, in speaking of the golem, as “a special kind of naked vitality.”

It is these marginals who—by virtue of their very marginality!—seem to hold the key to the mystery of Hafftka’s art. It is they who have been elected to secrete his paintings’ untellable tale. In fact, Hafftka seems to have the sort of relation to all his creatures—but most potently and poignantly these meagre existents—that the medieval Kabbalist had to his golem. As Gershon Scholem notes in The Kabbalah and its Symbolism, golem-making is dangerous not because of the overwhelming and unstoppable powers emanating from the golem cum sorcerer’s apprentice but because of “the tension which the creative process arouses in the creator himself.”

It is these marginals who—by virtue of their very marginality!—seem to hold the key to the mystery of Hafftka’s art. It is they who have been elected to secrete his paintings’ untellable tale. In fact, Hafftka seems to have the sort of relation to all his creatures—but most potently and poignantly these meagre existents—that the medieval Kabbalist had to his golem. As Gershon Scholem notes in The Kabbalah and its Symbolism, golem-making is dangerous not because of the overwhelming and unstoppable powers emanating from the golem cum sorcerer’s apprentice but because of “the tension which the creative process arouses in the creator himself.”